In the article, Keller explained it this way: “The desertification of the Sahel might not appear so dramatic if one were to compare the desert’s reach in 2022 to its reach in 2020. But comparing it to …1980 would reveal a stark transformation.”

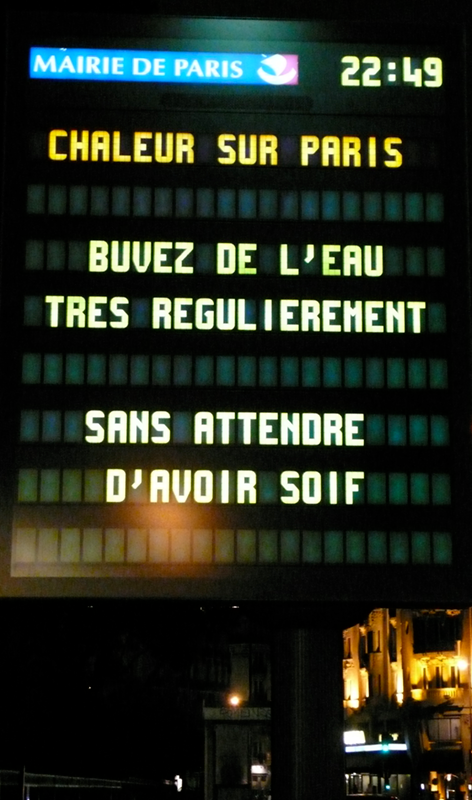

It’s the same with dangerous heat waves in France, which were once so uncommon that most buildings still do not have air conditioning. Now heat waves occur with increasing frequency. Since 2003, French officials have calculated heat mortality by averaging the number of deaths occurring during the same period (say, two scorching weeks in July) over the three previous years. They then subtract that average from observed deaths during the crisis period. The difference is the official excess death toll, and those deaths are ascribed to heat.

Keller’s article argued that climate change — and the COVID-19 pandemic — have made this method almost useless.

“Every summer in Europe, now, is getting unbearably hotter,” said Keller. “If you are using excess deaths as a tool for measuring heat mortality, you are looking back three years to get your average. But what happens when those numbers are elevated every year? Excess deaths are baked into the background data, and the baseline shifts.”

Shifting baselines can lead to underestimating the impact of a disaster.

Keller, who chairs the Department of Medical History and Bioethics in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, works closely with epidemiologists and demographers and relies on their quantitative research to create the big picture.

“I use those numbers as a way into a problem,” he said. “As I start looking at big-picture data, I find I have questions that the data don’t answer.”

For example, a question arose when Keller realized that the COVID-19 pandemic had likely affected the French population’s vulnerability to high heat.

“People can only die once,” Keller pointed out. “COVID-19 took thousands of vulnerable French people who might, had they not died from the virus, have been victims of the record-breaking heat waves in 2022.”

In other words, while the official assessment is that the 2003 heat wave was the worst weather disaster in contemporary European history, it is quite possible that other heat waves since then have been just as deadly. Keller supports a new method for calculating heat mortality that compares daily temperature data with total mortality. This method was proposed by Mathilde Pascal, an epidemiologist at Santé publique France, the country’s public health agency. The method, which doesn’t rely on past averages or on the government’s definition of a “heat wave” (three consecutive days of extreme heat), reveals that heat-related deaths are happening in dramatically higher numbers than excess mortality measures suggest.