Study finds analyzing DNA in urine could help detect cancer

A study published this week in Science Translational Medicine describes how urinalysis could potentially be used to detect some forms of cancer.

On Jan. 27, 2021, a group of experts in virology, infection control, global health, clinical testing, vaccine development, and health system responses took part in a virtual panel organized by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health titled “Hot Topics in Public Health: The Coronavirus Pandemic at One Year.”

Late January marked 12 months since the first patient with a then-unnamed novel virus sought treatment at UW Health. Since that time, the pandemic has shaped nearly every aspect of the school’s activities as researchers turned their attention to SARS-CoV-2, educators transformed instructional efforts to different modalities, and clinicians navigated the complexities of providing care in the context of a devastating and easily transmitted pathogen.

The eight panelists shared perspectives ranging from success stories to lessons learned from their experiences over the past year. Taking questions from the audience, the conversation covered the emerging virus variants, the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of color across the state of Wisconsin and beyond, the rigor and speed of vaccine development, misinformation about the pandemic, and more.

“We have such a deep well of expertise here at the university that we’ve been able to call on to help the state learn and understand these critical new topics and to collaborate scientifically in ways that benefit everyone,” said Ryan Westergaard, MD, PhD, MPH, a professor of medicine who also serves as chief medical officer and state epidemiologist for communicable diseases for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. “The willingness of scholars and researchers across the whole spectrum of basic scientists, social scientists and data scientists to give their time and talents to support the mission of public health has really been inspiring.”

It wasn’t the first time these experts had gathered. In January of 2020, they had convened for a public talk just as the novel coronavirus was emerging, which kicked off an unimaginable year — filled with both pain and progress.

The emergence of the novel coronavirus and the COVID-19 pandemic that quickly enveloped the globe made 2020 a challenging year for all. Members of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health answered the call during this public health and medical emergency. The school was ready and willing to help Wisconsin, the nation, and the world navigate and overcome the still-raging pandemic.

Here is how the school’s response unfolded, as told from the January 2020 panel to the January 2021 panel.

School experts wasted no time in gathering to exchange ideas and inform others on emerging questions and concerns about the novel coronavirus. In January 2020, the school was set to host Robert R. Redfield, MD, who was serving at the time as Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Redfield had to cancel at the last minute to attend to official duties. Instead, the school brought together nine experts to discuss what the SARS-CoV-2 virus meant in a Coronavirus Public Health Symposia. The room was packed with audience members and every local news station. Just weeks later, a gathering of this size would become impossible.

Long-standing scientific partnerships within the school and across campus sprang into action as early as February in the form of early research to understand and thwart the virus. Collaborators were discerning as many details about the new virus as possible, tapping their current research and building on successes from studying the Zika virus in 2016. The work would continue into the summer to include how to develop simple and quick COVID-19 tests.

The phrase “physical distancing” entered the public lexicon and researchers rushed to help push information to the public on the effectiveness of mask wearing. Scientists and public health experts were busy finding ways to keep people safe.

Datasets emerged as key resources for experts. In April, the Health Innovation Program, a health systems research program within the School of Medicine and Public Health, delivered maps with zip code-level detail on risk of COVID-19 complications across Wisconsin. This information is being used by more than 250 state, local, and tribal health departments, academic institutions, and professional organizations across Wisconsin to inform their public health decision making. Other valuable data gathering and reporting initiatives include work by researchers with the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) to estimate the percentage of Wisconsin residents with evidence of recent COVID-19 infection.

As infections rose in Wisconsin and nationwide, the disproportionate impact on communities of color became alarmingly clear, with Black, Latinx, and Indigenous populations significantly over-represented among COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths.

Through a rapid-response grant program, the Wisconsin Partnership Program asked for proposals in March to support work and help respond to the immediate challenges of the pandemic. In late April they announced 22 awards totaling $2.7 million for both research on COVID-19 and community-led organizations leading the fight to address the health needs of Wisconsin’s diverse urban and rural communities. These grants have increased and now total $3 million across 25 awards. The community grants focus on providing resources to vulnerable populations heavily affected by the pandemic. They funded projects focused on keeping individuals experiencing homelessness safe, addressing food insecurity, and providing culturally appropriate public health information.

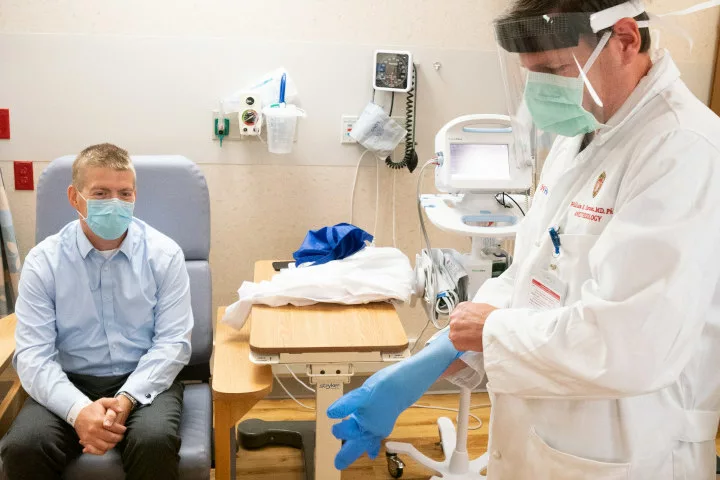

The school drew on its robust research infrastructure and collaborations to initiate clinical trials to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. In April the first COVID-19 patient at University Hospital was treated with plasma from a recovered patient in a clinical trial led by William Hartman, MD, professor of anesthesiology. The trial recruited individuals recovered from COVID-19 to donate blood plasma. The treatment has shown promise in helping ill patients recover and is currently in use.

A flurry of activity in clinical trials over the summer in June and July demonstrated the agility and research prowess of clinical trials professionals at the school and UW Health, producing critical data.

These two studies were supported by Wisconsin Partnership Program COVID-19 response grants:

At multiple stages of the pandemic, the school and community were reminded to make a positive impact by donating plasma as the stores of convalescent plasma that can be used to treat ill patients began to run dry. Plasma from recovered individuals is rich in antibodies that may help others fight the disease. Whether from UW–Madison students or health care providers, each reminder to the public about the importance of donating blood plasma if they have recovered from COVID-19 was met with resounding levels of selflessness, empathy, and a willingness to help save lives.

One of the school’s most-read articles of the year details research published in April on how certain types of respiratory allergies, asthma, and controlled allergen exposure were associated with significantly reduced gene expression in a protein that the coronavirus uses to infect cells with COVID-19. This suggests a possible reason why people with a respiratory allergy and asthma unexpectedly did not seem to experience some of the more severe and life-threatening manifestations of the COVID-19 disease.

A breakthrough in October was aimed at speeding up diagnosis of COVID-19 induced pneumonia. School researchers devised a custom artificial intelligence algorithm that can identify cases of COVID-19 induced pneumonia based on automated analysis of chest radiographs (X-rays). This ability to screen patients quickly for COVID-19 infection can speed up diagnosis, allowing better patient outcomes.

In late August, spirits ran high over the announcement that the school and UW Health were selected as one of the first U.S. sites for a phase 3 clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca. The vaccine has now been approved for emergency use in the United Kingdom, India, and Mexico, and the European Union.

As the number of people infected with the virus soared in the late fall, leaders of the two medical schools in the state penned an op-ed in December, addressing the people of Wisconsin directly with an urgent and lasting message — Take action: everyone has the power to save lives by taking a stand against the pandemic.