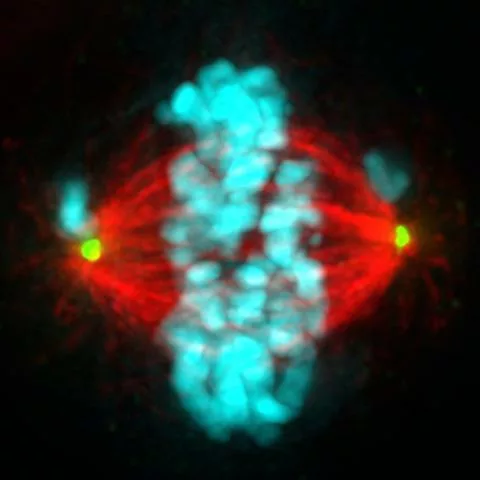

This chromosome shuffling could grant growth and survival advantages to some cells, which likely contributes to the development of cancer. Therefore, the UW research team thinks this is an important step in how HPV infection leads to tumor formation.

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and was under the guidance of the study’s senior author, Beth Weaver, who has a doctorate in biomedical sciences and is a professor of cell and regenerative biology at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

The most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States is HPV, and it causes 70% of head and neck cancers in the oropharynx, 90% of anal cancers and almost all cervical cancers, according to the National Cancer Institute.

“The good news is we have a vaccine against HPV, which protects against the nine major types of HPV that cause cancer,” Cosper said.

However, only 55 to 60% of people have received this vaccine in the U.S., according to Cosper.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Gardasil, an HPV vaccine, for all genders ages 9 to 45. Two doses of the HPV vaccine are recommended for children ages 11 or 12.

“I really urge people to get this vaccine and get this vaccine for your child, it could save their life,” Cosper said.

Cosper is also a physician-scientist in radiation oncology who treats cancer patients at UW Health Johnson Creek Cancer Center. In the laboratory, her research investigates ways to exploit a cancer cell’s inherent defects during division to promote cell death, which could lead to tumor regression. She is currently working on how chromosomal instability affects a cancer cell’s sensitivity to radiation.

The goal of this ongoing research is to discover biomarkers that could create more personalized treatment for head and neck cancer patients, she said.

Other members of the UW Carbone Cancer Center involved in the study include Randall Kimple and Paul Lambert; other UW researchers on the paper are Laura Hrycyniak, Maha Paracha, Denis Lee, Jun Wan, Kathryn Jones, Sophie Bice and Kwangok Nickel.