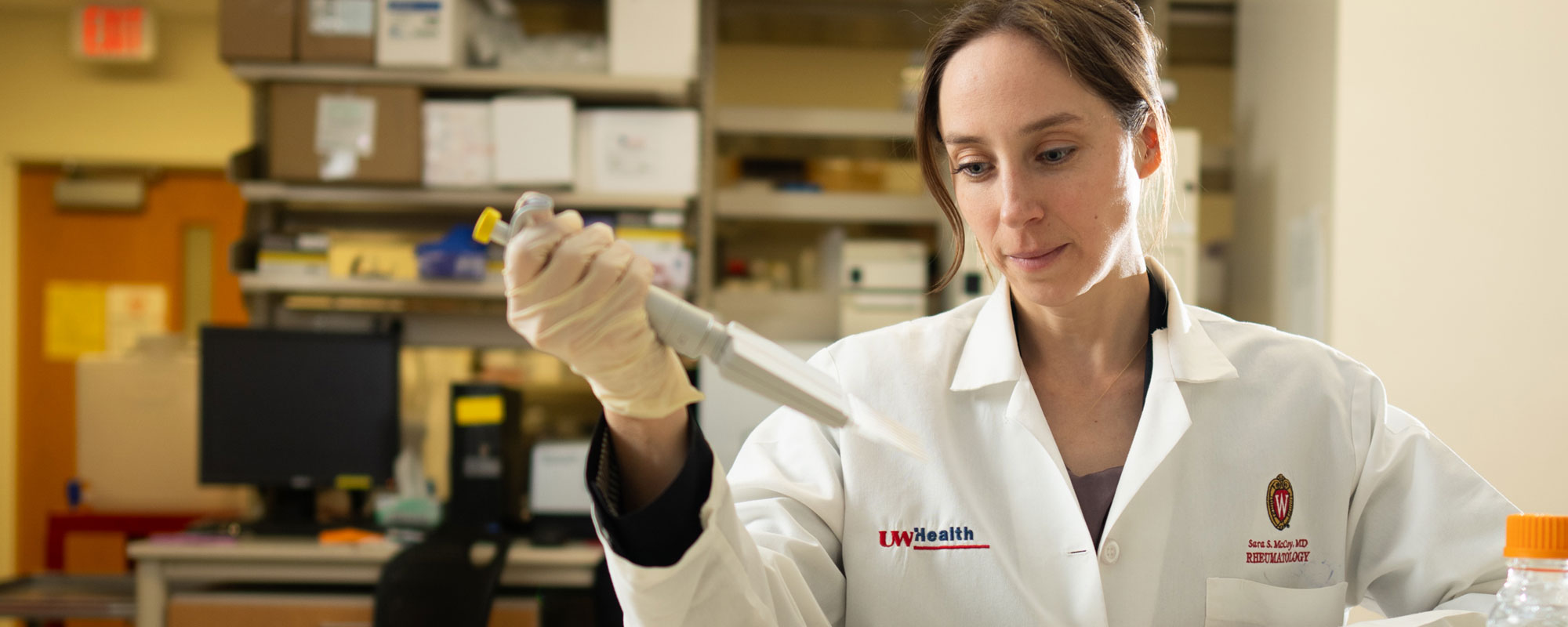

McCoy wondered if the use of a patient’s own enhanced stem cells could be used to improve salivary gland function in Sjögren’s disease patients and began working with PACT to start a clinical trial. She received FDA approval to initiate the trial in 2023. The approach extracts cells from the patient’s own bone marrow, activates them and injects them into salivary glands.

“The current standard of care is not addressing the root cause of dry mouth for these patients,” she said. “With this cell therapy, we are hopeful we can do more than offer temporary relief and give these people back these critical human functions.”

This Phase 0 trial is enrolling six patients and will be followed by a larger Phase 1 trial to establish safety and dose levels. Preliminary data on efficacy will be obtained in a cohort of 12 participants in an expansion phase of the study. The trial is open to people 18 and older with graft-versus-host disease, which also impacts saliva production, or Sjögren’s disease. Each participant will be given the therapy once, and the results will be tracked by McCoy’s research team for about two years.

While the goal of the first phase of the trial is to show that the therapy is safe, McGowan said she has noticed some improvement.

“I had been taking several lozenges a day to help with my symptoms, but after the treatment I used them once or twice a week,” McGowan said.

Sjögren’s disease impacts women more than men, about eight to one, according to McCoy, but there seems to be a lack of awareness of this condition, McGowan said.

For this reason, she has found participation in the trial to be a meaningful opportunity to help spread the word about the difficulties Sjögren’s patients experience, she said.

“I want to increase awareness of the disease and what the symptoms are so others don’t suffer,” McGowan said.

Read more about what sparks Dr. McCoy’s drive to innovate at UW–Madison.

Banner image by Clint Thayer, courtesy of the UW Department of Medicine