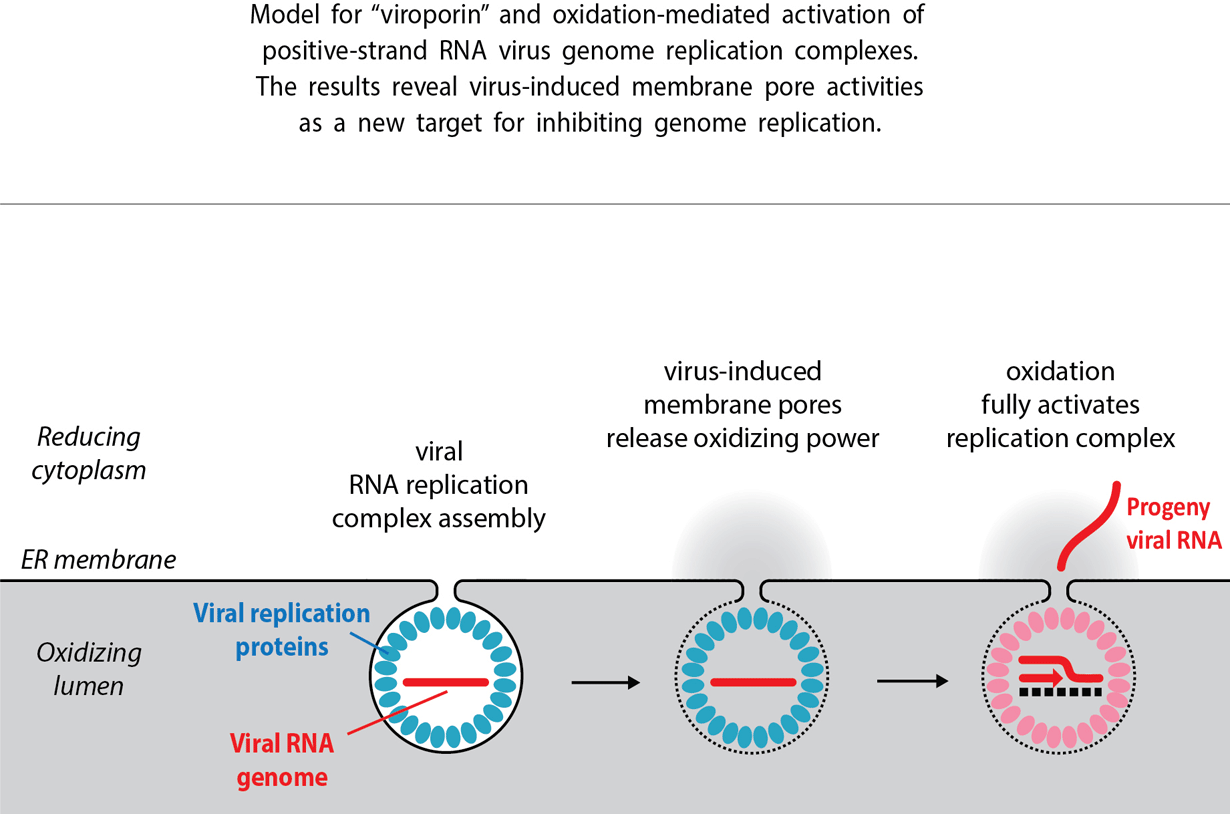

In order to spread throughout the body, viruses highjack normal cell structures and functions to achieve their own ends. This class of virus, for example, always anchors its genome replication process to the membrane surfaces of cell organelles. It had been understood this process occurs solely on one side of the membrane, outside of the organelle, in the cytoplasm.

This study reveals the conventional view is incomplete. Nishikiori found that an enzyme called ERO1, which resides exclusively inside the organelle, on the opposite side of the membrane, is crucial to promoting the cytoplasmic viral replication process. Reduce ERO1 and viral replication goes down, and vice versa, Nishikiori says.

The surprise was: How could an enzyme that was walled off from the virus by a solid membrane barrier activate viral growth? This was their first clue that something must be bridging the membrane. When combined with other insights, the team discovered that a key viral protein builds a pore or pipeline across the membrane, enabling ERO1 to affect viral replication on the other side.

Nishikiori previously found that the proteins creating these pores become strongly linked together by a kind of covalent bond called a disulfide bond. Most protein interactions are non-covalent, such as the attraction of positive and negative ionic charges, and are easily pulled apart. Covalent interactions are welded together in a much more durable chain.

However, disulfide bonds can only be created in an oxidized environment. The interior of many organelles is oxidized; however, the cytoplasm where genome replication occurs is non-oxidized or, in chemical jargon, “reduced.” Nishikiori notes that oxidation is toxic to many cell functions, which is why it’s isolated to certain portions of the cell.

This explains at least one purpose behind the pores, Nishikiori says. They allow delivery of oxidizing power into the cytoplasm to form the covalent disulfide bonds. “When the viral protein creates this pore, it allows oxidants generated by ERO1 to leach into the cytoplasm and create a plume of oxidizing power,” he says.

Ahlquist speculates that the virus may use strong covalent disulfide linkages to keep the viral genome replication apparatus intact. Drawing on other recent findings, he says viral replication complexes inside cells are under significant pressure and at risk of breaking off before replication is complete. The covalent bonds might be similar to the wire cage holding the cork in place on a champagne bottle, he says.

Basic research on the mechanisms of viral replication is essential to the larger quest to find broad-spectrum antivirals – or drugs that attack a wide range of viruses, Ahlquist says.

“When you apply an over-the-counter anti-bacterial cream to a child’s scraped knee, it works even though you don’t know exactly which bacteria you’re fighting,” he says. “We don’t have anything like that for viruses; most of our antiviral vaccines and drugs are virus-specific. We need new approaches that target broadly conserved viral features to simultaneously inhibit many viruses.”